I was shocked and saddened this week to learn my greatest mentor and dear friend, Clayton Makepeace, has joined the choir electric.

Prior to meeting Clayton, I was a novice at the craft of copywriting and shocked out of my socks when he took me under his wing.

I’m sitting there and the phone rings, which I typically ignore, but for some reason I picked it up and it was HIM!

Weeks earlier I had interviewed Clayton (by text) and he had given me such a kick-ass interview that I immediately jacked a picture of him on his Harley and put it on a squeeze page with an incendiary headline and started advertising it on AdWords.

I guess he had been Googling himself and saw it.

So he says through the phone…

“Mr. Levis, I see you’ve been using my likeness without permission.”

A long silence ensued as my sphincter tightened.

And then he laughs into the phone and recruits me to help him launch a new website, called, The Total Package, which went on to become the most read blog on copywriting in the known universe.

The next thing you know I fly down to meet him at his home in the Smoky Mountains, where I learn the ultimate copywriting secret…

The next thing you know I fly down to meet him at his home in the Smoky Mountains, where I learn the ultimate copywriting secret…

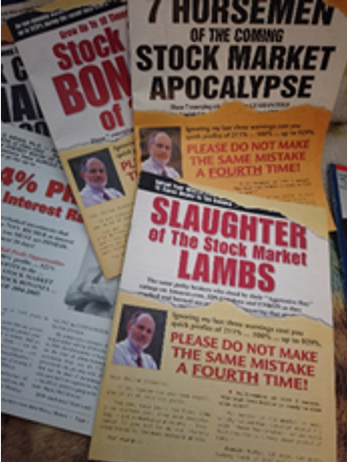

He had converted a store in downtown Waynesville into an office. And I was sitting in a special room with million-dollar packages strewn everywhere when he walks in and says, “look at this…

“…I call this Whole Brain copy”.

You see, the real power that Clayton possessed and the real reason his copy pulled like gangbusters was his unique flair for hair-on-fire emotion… combined with meticulous, thoroughly reasoned argument.

You read the copy and your emotions were inflamed… but instead of catching yourself with the typical “yeah right” reaction to over-the-top hype… you kept getting more and more excited the more you read.

Anyway…

One of the things we planned to do together was the Steal These Secrets Swipe File, a massive package of his biggest winners.

So he had me over to his house for dinner, where I did something I doubt he ever forgave me for…

We’re out in the garage having a couple brewskies, and off in the corner was a big safe.

We’re out in the garage having a couple brewskies, and off in the corner was a big safe.

“What’s inside?”, I asked.

“Guns”.

“Cool, show them to me”.

And he pulls out an AK 47 assault rifle.

The next thing he knows I’ve stuffed the safe with direct mail packages and I’m snapping a picture of him standing guard over the safe with the AK47 and an eye patch over his left eye. A pic, for the Steal These Secrets sales page.

It was the best metaphor for communicating the immense value of having dozens of direct mail pieces that had mailed in the millions as copywriting idea starters.

It was also the worst metaphor because a couple days later when he saw the pic, he said, “I look like an asshole”.

What he really meant to say was that he had the biggest heart in the whole wide world and wanted to help as many aspiring copywriters as he possibly could.

And that was him.

I’m going to miss you, bro.

You changed my life.

Reprinted below is the interview I did with Clayton.

It’s incredibly generous and filled with more secrets than most courses you’d pay hundreds for.

Read it and weep …

Daniel Levis – I‘m continually fascinated by the amazing variety in the backgrounds of people who find themselves writing copy for a living. In many cases, necessity has been the mother of invention, and I think it was Gary Halbert who summed it up best when he said something to the effect of, ―I look at teaching people to write copy as saving their financial lives. Because if you don‘t knuckle down and get this, do you know what‘s going to happen? You‘re going to have to work for a living, and it‘s going to KILL you! Leave it to Gary to put it so eloquently. So tell me the story of those early days, what were you doing before you began, what events lead up to your indoctrination into the world of copywriting and direct response marketing?

Clayton Makepeace – In 1974, I was working as a freelance film cameraman, doing TV commercials, industrial films and TV programs in Hollywood. A major recession struck, and work was impossible to find. So I began looking for another line of work.

I spotted an ad in the paper, run by a small direct response agency that was looking for a copywriter. I figured I‘d written lots of copy for TV, so I applied.

The owner of the agency asked me to audition by writing an eight- page fundraising letter for a mythological charity. I wrote the copy in an afternoon, and showed it to the agency‘s owner the next morning and he hired me on the spot.

Before I left his office, he handed me an arm full of books on the art of writing ad copy by people like Rosser Reeves, John Caples and others. I went home and devoured the books over a period of a week or two and reported for work ready to go.

Only one problem: The agency didn‘t have any creative clients. So, I wound up just working as a mailing list broker.

Then, one day, the owner offered me a nice bonus if I could build a million dollar creative agency in his company over the months ahead. I accepted the challenge and went to work banging on doors to find creative assignments from local businesses in the L.A. area.

At the end of about a year, we had a million dollars in billings and my boss refused to pay the bonus, so I promptly quit, took my clients with me, and have been on my own ever since.

Since those early days in the ‘70s, most of what I‘ve learned about copywriting has come either from trial and error or from studying controls that my competitors have created. I have been spanked by the best, and I‘ve beaten the best on occasion, and each one of those experiences has been extremely instructive for me.

It‘s a cliché, but my losers have taught me more than my winners. The contrast between the two, and being able to sit down and look at something that you wrote that bombed — and compare it with something for the same or similar product that was a wild success– is the best way that I know to internalize principles that will make each succeeding package stronger.

I also want to make the point that my early indoctrination into direct response marketing was not exclusively as a copywriter, although that was the purpose for which I was hired. I found myself researching the mailing lists that were best qualified to receive an offer for clients‘ products, creating mail plans for those clients, and then looking at their results to see how I could use selects or different kinds of lists to improve their response.

So in my first days as a direct response copywriter, I didn‘t write copy at all. I became a kind-of marketing manager for my clients. I even got involved in printing, and letter shop work, and personalization, and mail modes, and postage requirements. I had to do break-even analysis and create response tracking reports for many of these clients because in some cases it was their first outing in direct response.

So I got a solid, practical, working understanding of what our clients go through in order to test and plan their mailings, and what the financial criteria and performance criteria are for selecting controls. So it was a very well rounded beginning.

A lot of the copywriters I talk to today have no grasp of what happens to their copy once it leaves their hands.

Too many don‘t even ask the question, ―What are you trying to achieve with this package? When was the last time you called a client up and said, ―Look, are you trying to break even and bring in the most customers possible, or are you trying to produce a profit?

It‘s the single most crucial question on every project we do, and the answer will differ from client to client. Even on a customer acquisition piece that you‘re writing for outside use, sometimes you‘ll find that the customer has no intention of breaking even on the package. His intention is to make a profit on each new customer he generates.

As a copywriter, you do not want that client!

Once, after I had written a series of packages for Danny Levinas at Georgetown Press, Danny came to visit me in Florida. As we were talking, he said something that absolutely stunned me. “I don‘t want to be very big,” he said. “I don‘t want the headaches that go along with that. I‘m not looking to be aggressive in the mail.”

Well, since my income comes from royalties, that was the worst possible thing he could say to me. That was the end of our relationship. I had no interest in writing for him again.

What he was saying was, “You can write the best copy that‘s ever been written for any product and I‘m not going to mail maximum quantities because I don‘t want to be big. I‘m not aggressive. I don‘t want to take the risk.”

So knowing what the client is trying to achieve with a package he‘s assigning to you is absolutely critical, and understanding which clients are going to give you the opportunity at maximum royalties and which aren‘t is critical.

If a client says my goal is to make a 20% profit on every new name that comes in, he‘s going to mail fewer pieces than a customer who says I‘m willing to lose 20% on every new name that comes in. And that directly affects how big the sparkles are that you can buy for your spouse in the year ahead.

So getting a grasp of the nuts and bolts of direct marketing will make you a lot more money in the years to come.

Daniel Levis – One of the things I think a lot of people misunderstand about copywriting is the amount of research that goes into it, versus how much of it is actually putting pen to paper, so to speak. Suppose you had just accepted an assignment to write a sales letter for something you knew very little about. (Let‘s say some sort of new vegetarian diet, for the sake of example).

Can you describe the research process? How do you go about becoming knowledgeable in a hurry, before writing a lick of copy? What are your methods, in detail?

Clayton Makepeace – I‘ve been doing this for 33 years now, and had a lot of time to think about the process. I figure I don‘t get paid to do research, I get paid to write.

There are other people who are better researchers then I am, and every minute I spend researching is a minute I‘m not spending working on the persuasive and credibility of the elements of the text.

So in most cases I insist that my clients provide the research that I need. It‘s a win-win for them as well, because they‘d rather have me working on major parts of the copy, themes, offers, and so forth, than slugging through a bunch of books, or spending hours online.

Some clients don‘t have research departments available to them. In those cases I prefer to hire a researcher to do the bulk of the work for me. I begin by actually selecting the theme that I‘m going to be writing on, creating a copy platform, thinking my way through the package, and creating a research request.

Then, I send my research request to one of several researchers I‘ve used over the years and they go to work for me. In a week to ten days, I have a fairly complete research kit, all in digital format so I can copy and paste out of it into an outline document.

This saves me a couple of weeks on every project. In some cases, the researcher may be a junior copywriter, in others, it might be somebody who normally creates premiums for my clients for a living, and I use them for the research function.

Daniel Levis – One of the most important things I‘ve found in coming up with a successful sales letter or advertisement is the hook. Some kind of a big idea that dramatizes the item I‘m selling. Obviously I want to attract attention, and draw readers into the body of the piece, and inspire people‘s imagination. Can you tell me some of the techniques you‘ve developed over the years for mining those golden nuggets? I mean, what are some of the thought processes you‘ve found to be most effective in uncovering the hook? It would be wonderful if you could cite some specific examples as well.

Clayton Makepeace – When I’m looking for a hook or a lead of a package; I go one of three ways:

Possibility #1: If I‘m writing about a very straightforward product that delivers a benefit that is both powerful and unique, my copy is likely to lead with that benefit.

This makes the promotion piece look like just what it is: A promotion piece. There‘s a downside to that of course, because in today‘s world, my average prospect is getting more than 600 advertising impressions every day. By leading with the benefit of the product, I quite often run the risk of having my promotion being outed as a promotion, and therefore, not being read.

So if I‘m going to go with a straight benefit lead, I look for ways — both with copy and with graphics — to make it appear to be a value-added special report of some kind.

Possibility #2: The second way in is to think about how my prospect‘s feeling right now about the problem that my product solves, or the fear that it assuages. This ―feeling‖ is quite often referred to as the prospect‘s resident emotion, or dominant emotion.

Especially in the investment area, for example – also the health area – you can quite often get greater readership on the front end by addressing the problem or the desire that the prospect holds most dearly at the given moment, and not even looking at the product benefits upfront.

Possibility #3: The third way in is a topical lead. Especially if I‘m doing something for the Internet that‘s going to be delivered very quickly or a first-class direct mail piece, I‘ll quite often use a news story that‘s been on the front of Time, Newsweek or The Wall Street Journal.

If it‘s at the top of the news, it‘s on the top of my prospect‘s mind. And if he‘s thinking about it, he has feelings of either fear or desire about it.

I believe that emotion sells products, logic alone doesn‘t. So when you find a topic that‘s really hot, it‘s pretty much a slam-dunk that the prospect has strong emotions about it.

In the financial area, for example, the major trends have to do with things like rising interest rates, accelerating inflation, rising commodity prices, the possible bursting of the real estate bubble, and those kinds of things. Every one of my prospects has an opinion and a strong feeling about those things, and is concerned about how they might affect him adversely and what kinds of investment opportunities are there. So the topical lead is also a good way in.

Daniel Levis – Before putting pen to paper, most copywriters spend some time outlining what they are going to say, and how they are going to say it. How do you organize your thoughts? Do you have a specific method, maybe even a set of templates you‘ve put together over the years to fast track the development of the right outline for a given piece? Please describe the various essential building blocks that go into an outline, and some of the most important processes and constructs you use to develop them.

Clayton Makepeace – I don‘t work from a fixed outline, however. For a course I‘m working on now, I‘m putting together an excellent outline for short, medium, and long copy that‘s been very successful for me over the years. It‘s just a general guide for young copywriters and those just getting into the field.

I write mostly long copy packages – and the most crucial pages are the first three. Attention and conversion to readership are everything today because of the sheer number of promotions that our prospects are receiving.

So the first two, maybe three pages of text are quite often organized very differently from package to package depending on what the topic is, what the theme is, what the hook is.

In these cases, I tend to lead with stuff intended to sell the prospect on reading what follows — presenting reasons why he should believe and act on the information that follows. In other words, creditability elements: Who my editor is, what his background is, what his qualifications are, or citing reference from other credible sources. In the health field, for example, it could be Harvard University or The New England Journal of Medicine, or some other peer reviewed medical journal.

Then, I try to tease in the first couple of pages how this finding, or how this development, or how this trend could benefit the reader in some way, and the horrifying alternative — what will happen if he doesn‘t acknowledge the importance of this trend and take action to either protect himself or profit from it.

First, I recognize that

I’ll have to make 8 preliminary sales before the

phone rings or the check gets mailed.

And they are …

1. The ATTENTION sale: I‘ll have to sell my prospect on looking at my ad, direct mail piece or listening to my TV or radio spot.

2. The READERSHIP sale: I‘ll have to sell my prospect on reading what I have to say, and then, on continuing to read.

3. The BENEFIT sale: I‘ll have to give my reader every single reason why he should buy: Every benefit he‘ll get, every fear that will be assuaged, every desire that will be fulfilled.

4. The CREDIBILITY sale: I‘ll have to convince my prospect that my product really will deliver the promised benefits.

5. The VALUE sale: I‘ll have to convince him that the price I‘m asking in return for doing all these things for him is a pittance – hardly worth thinking about.

6. The SAFETY sale: I‘ll have to convince him that there is no downside to accepting my generous offer.

7. The CONVENIENCE sale: I‘ll have to sell him on how simple and convenient ordering my product is.

8. The DO IT NOW sale: I‘ll have to convince my prospect that acting now is more than just ―in his best interest – it is absolutely, positively the single most important thing he could do now.

Here‘s the general long-copy outline …

Grab ’em by the eyeballs: Seize your prospect‘s attention with a powerful benefit-based, emotionally-driven headline.

Support your headline: In a short deck, expand upon your headline with a deck structure that drives it home in a powerful way.

Bribe him to read this: Tell him what you‘re going to tell him. Trumpet any value-added information that you‘re going to give him free, in the copy.

Get his juices flowing: Open with a powerful, emotionally driven, benefit-based paragraph or two.

Make him believe it: Add credibility elements – a series of paragraphs presenting statistics, expert endorsements, track record info (if it‘s an investment product) or customer testimonials that prove you really can deliver the benefit.

Get back on track: You‘ve demonstrated what you‘ve done for others and what others say. Now, it‘s time to get back to talking about your prospect‘s favorite person: HIM.

Repeat your lead benefit and transition into your secondary product benefits, each written in a way that connects with the prospect‘s most compelling resident emotions – his dominant emotions.

If you have room, make each benefit a subhead, followed by two or three paragraphs of copy (or more) that dimensionalize it.

If you‘re cramped for space, turn each benefit into a bullet.

If you‘re somewhere in-between, lead with your strongest benefits as subheads with explanatory copy and bullet the rest.

Make an offer: Repeat your headlined benefit, allude to the others, present your offer, and justify your price.

Relieve risk, add credibility: Add your guarantee and point out that, since the prospect‘s delight is a sure thing, he has nothing to lose.

Sum up: Repeat your main headline benefit, the strongest secondary benefits, justify your price again, remind them of the guarantee and ask for the sale.

Show your prospect how easy accepting this offer is: ―Just complete and return the enclosed order form or dial TOLL-FREE 1-800-000-0000.

Close with a final reminder of your main headline benefit, what a steal it is, a mention of the guarantee. I also like to create word pictures of how the prospect will feel with the benefits my product offers – and without. There are consequences to declining this offer!

Sweeten the pot: I like using my P.S. to catch my prospect off-guard. Just when he/she thinks “This is a pretty good deal”, I like to add just one more thing to push this from a good deal into an absolute, deadlock-cinch no-brainer.

The best way to do this is by adding something to the offer: Usually an extra discount or a free gift for responding right away.

Add an urgency element: In a P.P.S., I like to give a final reason why the prospect should respond right now. This reason could be an extra bonus, or merely a rationale – like ―The Fed‘s going to raise interest rates on May 15 – whether you‘re ready to profit or not! Please – let me hear from you NOW!

Daniel Levis – I look at copywriting as a transfer of energy & passion. Personally, I need to get psyched up before anything worthwhile seems to bubble up to the surface. And it‘s challenging sometimes. If I‘m locked away in front of my computer for days trying to pump out a bunch of stuff in order to meet a deadline or whatever, sometimes it‘s difficult to find that spark. This is especially true for me when I try to rewrite something. How do you deal with this? What methods do you use to stay stoked, and fresh?

Clayton Makepeace – The answer is it‘s difficult sometimes. Especially if you‘re writing for an information product, and the copy and the product are uninspiring, or complex, or technical, and it‘s a nice day outside and I can hear my Harley calling to me.

The hardest thing in the world is to lock myself in the office and go through reams and reams of unbelievably boring material. I just had that experience with a particular client, and as a result, it took me several weeks longer than normal to create his promotion.

But I find that creativity is energy, and vice versa. Therefore, during the week my lifestyle habits are very important. I‘m 53 years old. I‘ve been doing this for a long time, and I find that my diet, getting exercise, and getting some fresh air and sunshine every day is essential in maintaining the energy levels needed to do this work.

Another thing that I find very helpful is that I usually rise at 4 AM, and I work until I find my attention span dwindling. Then at that point, I set the work aside and I move on to something else.

Another technique is based on a finding I heard early in my career, which was that each of us has two aptitudes, a creative aptitude, and an accounting aptitude. Some of us are nearly 100% creative, and some of us are nearly 100% accounting.

A lot of us have both aptitudes, and when we‘ve been using our accounting aptitude for days reading, researching, doing those kinds of things — quite often we hit the wall. When that happens, it‘s often because your accounting aptitude is depleted for that period of time, but the creative side of you is dying for an outlet.

So, quite often when I hit the wall on these kinds of dry, dull, boring research tasks, I set the work aside, open a new document, close my eyes, and just start thinking about themes, headlines, subheads, side bars, proof elements … the more creative side of the task.

This can add hours of additional work to a day, in which I‘d otherwise given up and gone fishing at 2 or 3 o‘clock in the afternoon.

One more thing: There‘s something that I learned when I first learned to ride a bicycle when I was a kid, and that‘s when you‘re riding along on a curb, if you look at the curb, you‘re gonna hit it. If you look ahead where you wanna go, that‘s where you‘re gonna go and you‘ll avoid hitting the curb.

Thinking about deadlines is the worst thing you can do. I know our clients hate to hear this, but to me, a deadline is just an indication of how late the work is going to be — or how much earlier than he expects it‘s going to be, but I can‘t allow it to drive me.

I can‘t allow it to push me into decisions that are going to hurt the copy and hurt the promotion. Jim Rutz once told me something I‘ll always remember: ―The heartbreak of a blown deadline is soon forgotten in the warm glow of a hot new control.‖

Absolutely true. Think about deadlines, and you‘re going to find that your copy suffers. Focus on writing the best copy you can and deadlines may suffer sometimes, other times they won‘t, but you‘ll get a lot more winners.

Daniel Levis – I don‘t know if there is any definitive answer to this question, but it is certainly a very important, and fundamental question I hope you can comment on. Based on your experience and testing, when does it make sense to use a two-step or even multiple-step process, versus a single step “go for the jugular approach” in your advertising? When does it make good business sense to try and generate expressions of interest, by offering some kind of a free report or something (in order to gain a lead you can then follow up on), versus driving for the sale? And are there any circumstances where you feel it makes sense to do both with the same piece of copy?

Clayton Makepeace – There are two parts to this answer. The first part‘s a marketing answer; the second part is a creative answer. They have to work together.

The marketing answer is: A two-step program makes sense when you have a product with a high enough margin to justify the cost of multiple steps, or when you have a medium that‘s so low a cost that the number of steps don‘t matter.

From the creative side, I use multiple-step programs in two ways:

Way #1: When I have a huge but not well-defined mailing list, or email list, or other media, I use a first step to call out my customers from that huge market place, and the second step to sell them.

Way #2: When I have very inexpensive media and a captive audience. A couple of years ago, for example, I had a new product for an investment advisory that sold for $1,000 a year. My client had 150,000 customers on his email file.

I decided to make the introduction of the new product a Gala Event. I cleared the decks of all promotions to those house file names for 30 days, actually 45 days, and then I created weekly, then daily promotions for the file on the new product.

I began with a print insert in the client‘s newsletter announcing the product, followed with a daily email blast, each of which led to a landing page with long copy, selling the product.

The following week, we had a First-Class mailing of a special report format piece, promoting the product and followed it with a new volley of email blasts.

The next week, we did a #10 personalized letter to the entire file, wondering why the customer hadn‘t ordered, followed by email blasts.

… And so on, for five full weeks.

The campaign generated $5 million in sales in a little over five weeks.

Daniel Levis – I think you would agree with me when I say the voice you use in a given piece of copy is critically important, and it should resonate with the market your sales letter or ad is targeted toward as closely as possible. For example, if you are selling to car racing enthusiasts, the more you use trackside language in your sales copy, the higher your rapport and therefore conversion. So in some ways, you are like an actor getting into character. What methods do you use to get into character quickly and effectively?

Clayton Makepeace – I don‘t worry too much about getting into character in the early drafts of the piece. After I‘ve done my research, and I‘ve dropped it into the proper places in my outline, I smooth it out into one cohesive whole, a sales letter, running text article, whatever.

At that point, because the research itself contains the jargon that my prospects are comfortable in a particular venue, I‘m in pretty good shape. Then, I just look for opportunities to work key phrases and words into headlines, subheads, and to punch it up in a copy.

At the same time, most of the things I do are related to health and investment subjects – and the jargon can be quite technical. If you go out with a package full of ten-dollar medical terms or highly technical investment, or economic jargon, you‘re going to have your head handed to you.

It‘s important to have a balance to make sure that the copy is understandable by the average guy on the street, but at the same time demonstrates your expertise through the selective use of jargon.

Daniel Levis – You‘ve just finished writing out a first draft on a piece of copy. Now it‘s time to edit. But here‘s the problem. You‘re too close to the copy. Are there any techniques you use to step out of yourself, and look at that piece of copy objectively, with fresh eyes when it comes time to edit?

Clayton Makepeace – After I‘ve written a first draft, I show it to my wife. She has a background in marketing, and yet, hasn‘t been deeply immersed for over a decade, so her insights on the copy are quite often very helpful to me.

Also, I like to show copy to anybody who will read it, whether they‘re a qualified prospect for the product or not, and just listen to what they have to say. Their impressions are important at the second-draft stage of the copy.

Probably the worst person to look at copy after the first draft is somebody who thinks they know something about copywriting, because they‘re not going to be looking at it with fresh eyes either. They‘re going to be looking at it with all of the little rules and other prejudices that copywriters have. I try to show the copy to people who are uninvolved in the direct response industry.

The question that I really have in my mind when I‘m showing them the copy is, ―Are they going to ask me where they can get this product as a result of reading this copy?

If they don‘t ask that question, if they don‘t say, “WOW! I really want one!” Then I know I haven‘t done my job, and I question them to find out what the reservations were and try to figure out what I could have done better to push them over the line.

So in essence, when I show a first draft to somebody, I‘m looking to make a sale.

Daniel Levis – Will you tell me the story of your wildest advertising success, and explain why you feel that particular campaign was so effective?

Clayton Makepeace – Some years back, I had been writing promotion packages for a publisher who had just started a new newsletter called The Money Advocate. We‘d been quite successful with the new subscriber acquisition packages we‘d been mailing. The newsletter was only a few months old and we were up to 30,000 subscribers.

After a new subscriber came in, the client would send them a promotion to sell them some rare coins. As I looked at these promotions, I felt that they were really weak, and asked the client if I could try my hand at writing the next month‘s promotion for him — no charge. I just wanted 5% of the revenues. He agreed, and I wrote the promotion.

Until that time, my client was averaging about $360,000 a month in sales to his subscriber file. My promotion pulled in $3.6 million in the next 30 days, or 10 times what he had been doing.

So naturally, he retained me to do all of his in-house promotions. By the end of the year, we were doing $16 million a month in sales to our subscribers — a 4,400% increase in revenues in twelve months.

What I did to produce that increase was very simple: The client had been selling rare coins to customers on the basis of their investment potential only. So his copy talked about how rare the coin was, how many other investors wanted to own one, how similar coins had gone up in value in the past.

To me, that copy was dry and uninspired. But when I looked at the coins he was selling, I saw something completely different. I saw history.

When I first held one of these old Morgan Silver Dollars in my hand, the first thoughts that went through my mind were about where the coin had been. ―What if this coin could talk? What stories would it tell?

I started thinking about what was going on in the United States in the mid 1800s when the silver in the coins was mined and when the coins themselves were minted. I conjured up images of the Wild West … the unsettled frontier and Indian fighters … casinos, and honky tonks, and bar girls. I wondered if Wyatt Earp had one in his pocket at the gunfight at the OK Corral.

At the end of this emotional, colorful, romantic copy, I included one, little box that discussed the rarity, the demand factor, and the investment potential of the coin.

Now, instead of appealing to remote greed – the possibility that someday you‘ll make money on this, or appealing to the customer‘s intellect, suddenly I was talking to his heart. And nine times out of ten, it‘s the heart that makes the purchase decision.

I remember telling my client at the time that the key is that the profit potential for the coin is the excuse the customer gives his wife for buying it. The reason he buys it is because it‘s cool.

I‘ve had many successes like that over my 33-year career. After leaving that client I quadrupled sales for another coin client in twelve months. After that, I went on to writing packages that generated 2 million new subscribers for a single newsletter at Philips Publishing International.

Next, I went on to quadruple a company in Palm Beach that published investment advice and research, and I‘m currently doing it again with a vitamin company that is now selling slightly less than $20 million worth of product a year. I predict within a year we‘ll be doing well over $100,000,000.

Each time I do several things. But it all boils down to helping them market their product with procedures that will get them bigger mailings more often, and then combining that with powerful sales copy that gives them bigger winners more often.

The combined effect is explosive growth and explosive profits.

Daniel Levis – It‘s been said selling is a transference of enthusiasm, and I believe that‘s true. Some would call this hype. Whatever you want to call it, it‘s a valuable tool but only so far as the promise responsible for generating that enthusiasm is credible and believable. What are some of the subtle techniques you employ to maximize the believability of the promises you are conveying in your copy?

Clayton Makepeace – I call these believability factors credibility elements, and I have them very carefully woven into everything I do.

I tend to go for the jugular when it comes to headlines, and if an investment product is generating 1,000% profits I‘m going to say so. I don‘t care if it‘s believable or not in my first and second drafts. What I care about is how well I can document it, and how credible I can make it using other elements in the text.

If an investment advisor comes to you and says, “I made a 1,000% profit for my clients last year, you‘re going to call him a liar.”

But if the promotion piece is in the voice of my client‘s customer, and if he talks about how skeptical he was up front … and how his wife thought he was crazy for even trying this … how he felt when his investment began taking off … how his skepticism slowly subsided … how he saw the numbers in his brokerage account soaring … how it felt to walk into a bank and cash a brokerage check for $1 million … and how it felt to use that money in ways that made his life richer … it is believable.

There are many ways to boost credibility. Testimonials can be used creatively to remove all doubt. I like to take testimonials and tear them apart; turn them into narratives. Even call the person who gave the testimonial and interview them to get details.

I also like to use testimonials as headlines. I recently created a promotion in which I had two headline tests. The first one was a straight benefit sale. The second was a testimonial headline, written by a customer who said, ―Heart surgery may be obsolete!‖ The testimonial headline out pulled my benefit-oriented headline by more than 50%.

I also like to put my client‘s PR departments or agents to work for me. I want to see my clients on television. I want them to write books. I want them to submit articles to notable magazines … to websites with big names … and to The Wall Street Journal, Barron‟s, Forbes and Fortune. I want clients who are advocates for health products to be published in The New England Journal Of Medicine and The Journal Of The American Medical Association.

Then, I have a sidebar where I actually have pictures of publications that have featured my client and pictures of my client on Nightline or on 60 minutes, or on some other notable television program; Neil Cavuto or on CNN.

Guarantees can also be great credibility devices. A lot of copywriters think of the guarantee as a risk reliever, pure and simple. They‘ll simply say something akin to, “If you don‘t like it we‘ll send you your money back.”

But a guarantee can be much more than that. A guarantee can be proof that you‘re absolutely convinced that your customer is going to love this product.

There‘s no percentage in buying something just so you can get your money back. There is a percentage in buying something that the seller believes I‘m going to love so much and is going to make my life so great that I‘ll never exercise the guarantee.

I also look for third party research that supports every one of my client‘s claims. It‘s not enough just to say, “Research shows that vitamin D does this, this, and this” I‘m looking for Harvard University to give my client a tacit endorsement by saying, “Vitamin D deficiency will kill you. If you have ample vitamin D in your system, you‘ll never have a heart attack.”

For investment and financial products, the advisor‘s track record is a central credibility device. A lot of copywriters just default by putting up a table showing the stock they bought when they bought it, how much money they made, and how long they were in the investment. That‘s the lazy copywriter‘s way to poverty.

I like to turn each trade into a narrative: Talk about how the advisor found the stock and why he liked it. Then, I tell the story about how he begged his subscribers to buy it … reminded them repeatedly … told them it was gonna take off. Then I show how it took off … how much money they made … how quickly they made it … and when they closed out the trade. Then, I like to humanize it by showing what some of his subscribers did with the money they made.

Another way to lend credibility: In pre-heads for promotions for financial products, I like to have a pre-head that says, “From John Smith, the only advisor in America who earned 10% for every 1% rise in interest rates” or some other wonderful thing that this advisor has done.

Finally, after I‘ve finished the copy and I have all my credibility devices in place, I print it out, sit down, and read the entire thing, even with the huge headline promise on the front, and I try to sense whether or not the headline promise is now believable because of the credibility elements I‘ve added.

If not, then I may soften it some.

Daniel Levis – In your opinion, what are the three most powerful human motives to work on in your copy, and why? And how do you go about getting into the head of a specific type of buyer, so you know which buttons to push for maximum response?

Clayton Makepeace – Instead of thinking about “motives,” you should be thinking about emotions. Motives are intellectual in nature. “My motive is to make money.”

Emotions are the overlay for the motive. They‘re what gives motives legs and generate action.

In my mind, all actionable human emotions fall into one of two categories:

1. Fear of a possible future event. Fear can range in intensity from concern … to worry … to terror … to outright panic (https://orderklonopin2mg.com/diazepam/). The higher up the scale the prospect‘s fear goes, the more effective it is as a motivator.

2. Lust. Lust can also range in intensity – from a wish … to a―want … to greed … to a craving … to an obsession. And again – the stronger the lust your customer has, the more it will motivate him.

Daniel Levis – In your experience, all things being equal, where are the best places (i.e. headline, lead, offer, guarantee etc.) to begin split testing alternative insertions in a piece of copy, generally speaking?

Clayton Makepeace – No contest. The two parts of your copy that give you the greatest opportunity for a bump in response are…

1. Attention-getters and readership converters – your headline, deck, and opening copy. I‘ve seen headline tests produce 50% lifts and even more.

2. Offers – your price, premium, guarantee. I‘ve often seen an offer test give a 20% to 30% lift.

Of the two, I spend far more time testing headlines and opening copy. And I‘m looking for more than a lift. I‘m looking for headlines that I can rotate month to month so as to reduce the attrition in response that occurs when you‘re mailing the same package to the same people, month after month.

Having three or four covers for self-mailers or envelope teaser structures for component packages can make the rest of your copy last months, even years longer.

Daniel Levis – One of the biggest things marketers struggle with is differentiation. What creative ideas would you offer someone trying to build a Unique Selling Proposition for a very mundane product or service that doesn‘t really offer anything unique?

Clayton Makepeace – If you don‘t have something that‘s absolutely unique about your product, there are two things you can do:

You can go to your client and say, “Hey look, I can sell ten times more of this product if you make this one change to it.” In some cases, especially in the information industry, you‘ll find the client excited about your suggestion and they may actually implement it. Problem solved.

The other way to do it is to advertise a benefit of your product that competing products just don‘t advertise.

Example: In the early 1900s, the great Claude Hopkins was charged with the task of creating an advertising campaign for Schlitz beer. But try as he might, he couldn‘t find one thing about Schlitz that made it unique.

Hopkins‘ solution: He toured the brewery and took copious notes. Then he wrote about the pains that they took to produce their beer.

He talked about how they used the purest water, the best quality hops, how they took more time with their beer to make it perfect.

By advertising these things – things none of his competitors had advertised – Hopkins convinced his prospects that Schlitz was the only beer made this way.

Daniel Levis – What advice do you have for new market entrants? How can someone with little or no track record enter a market with a new product or service and profitably compete with entrenched players?

Clayton Makepeace – Work for free. About a quarter-century ago — back in 1980 — I went out on my own for the first time. I had no name, no clients and about $90 in the bank.

One day, I happened to see a particularly weak promotion piece being mailed by a small newsletter publisher.

So, I called the publisher from a phone booth and said, “Mr. Johnson? My name is Clayton Makepeace, and frankly, your sales copy sucks.”

When he stopped laughing, I explained: “I write direct response sales copy, and I just saw the promotion for your newsletter, Daily News Digest. I‘m so sure I can double your response, I‘m willing to write a promotion for free.”

Here‘s the catch, I said. “If I beat your control, you pay me $1,000. If not, it‘ll cost you zilch.”

At the time, copywriters were getting about $800 for a promotion package — no royalties. So my $1,000 demand was a bit high. But what did he have to lose? If I beat his control, he‘d make money. If I didn‘t, he didn‘t have to pay me a dime.

Well, I did beat the pants off his control, and it was the beginning of a very long and very profitable relationship. That one client supported my family for four or five years. And my successes with him gave me a name in the industry.

If you‘ve got your chops and find someone you can really do a good job for — beat whatever he‘s mailing now — offer to work for free, and give yourself a nice huge perk if you beat the control.

You‘ll end up not only with a nice chunk of change, but you‘ll also probably end up with a client that‘ll be with you for years and that you‘ll be able to establish your name in the business by working for him.

Another way to do it is by simple networking at industry conferences. I‘m not talking about going in and stalking the halls for anybody who looks like a client. What I‘m talking about is meeting senior copywriters.

I quite often take on more work than I can handle, and I do it intentionally. Over the years I‘ve built up a crew of younger copywriters I mentored, and every one of them has since become quite successful.

It‘s a win-win for everyone. I was able to put out more packages per year than I would have otherwise, and so I made more money. The young guns got great experience and made money. The client gets all the packages he needs.

Daniel Levis – OK, closing question, thinking back over your career to date, what was the single biggest income-boosting aha moment… the one idea, technique, or revelation that made the biggest difference in your results from that point forward?

Clayton Makepeace – Ah … question fifteen – I love this question, because I‘m on a crusade and here‘s why …

The freelance copywriting model that everybody‘s following is just plain nuts. It‘s the worst possible arrangement for clients, and it‘s the worst possible arrangement for copywriters.

A copywriter who‘s doing freelance work has a new client and a new product every month. That means a new learning curve, a new set of research, and having to learn how to work with a new set of people – every month for the rest of your life.

Every minute copywriters spend doing those things is time that you‘re not getting paid for. Working on a freelance basis costs copywriters money.

For the business owner or marketing exec who uses copywriters, it‘s just as bad. There are never enough copywriters. Every time he gets a new copywriter on board and sees their first draft copy he has the same crits, because the copywriter doesn‘t understand his compliance guidelines … his experience in the mail … the specific product‘s testing history.

And because of the arm‘s length arrangement – because he knows the writer will be working for his competitor next — the client really can‘t share that kind of proprietary information with the writer.

So the client goes through copywriter after copywriter after copywriter and then calls someone like me, who can only take on a limited number of jobs per year, to complain that all the new copywriters suck.

Well the new copywriters don‘t suck. The new copywriters are new copywriters. They haven‘t had the long experience with each of these clients that more seasoned writers have.

I‘ve been writing for Phillips Publishing International since 1990. I know the people personally. The president, his top group publishers and marketing people came to my wedding. They send me pictures of their kids. I know exactly what they like, what they don‘t like, what they‘ll tolerate, what they won‘t, and because of our friendly relationship, I can cajole them, push them into testing things that they would never do for a writer they don‘t know as well.

So my crusade is to junk the freelance model, and convince our clients to try something new. Each of the four biggest successes I‘ve had in my career, at Security Rare Coin, Blanchard & Company, Phillips Publishing, and Weiss Research happened while I was exclusive with each company.

I spent no time each month beating the bushes for new clients. I spent no time learning about the client, his products or his market. I spent little if any time doing research because I asked these companies to research my copy for me. I was free to spend my time doing the one thing that made them the most money: Writing sales copy– not Googling everything that moved.

Each time, I was able to produce many more packages per year than I could when I had the learning curbs to continue it. Each time my win ratio skyrocketed. Between 1998 and 2003, I didn‘t have a single bomb for Weiss Research. Every single one of my new packages beat my old controls. At a time when other financial publishers were only able to mail 300,000 promo pieces every six weeks, Weiss was mailing 3 million. While other financial newsletters were shrinking, Weiss quadrupled its subscriber base. And while its competitors‘ profits were declining, Weiss‘ profits nearly tripled.

That‘s the kind of magic that only happens when you deepen the relationship between copywriters and their clients.

And there‘s another little piece of magic: The copywriter‘s income soars. You get bigger winners, more often. Your royalties skyrocket. Relationships like that earn me millions a year.

To me, the freelance model is patently insane: We‘re all doing the same thing over and over again and expecting better results.

When clients learn a new way to work with copywriters, in which they get the copywriters‘ best, then they‘re going to explode in size, but until then, they‘re going to continue being starved copy, and they‘re going to continue having these miserable win rates on new controls.

So thank you for giving me a soapbox to stand on. This was fun. I hope we do it again. Thanks.

This was an amazing thing ti post, i discovered direct response copywriting through claytons blog site it was like discovering buried treasure i couldnt wait to read every post, this stuff was all new to me and i knew it was valuable. He held nothing back. And tben i purched his swipe packages with those incredible dissections and analysis by another great mind whos name i had never heard of- daniel levis, those dissections crawled right into claytons brain to reveal mind blowing secrets ans strategies, im so thankful for tbe day i stumbled on that website i wish i could have met Clayton Daniel thanks for a great tribute

Clayton rest in peace

Thank you, John. Yes, Clayton was the best there is. He will be missed.

Awesome content, Daniel! Thank you so much for sharing. Condolences for your loss.

Clayton was good as gold. May he live on thru the successes you are coaching us to achieve!

Will always think of Mr. Clayton Makepeace as The Total Package. A great tribute. Thank you, Mr. Levis.

Yes Daniel, I remember well looking forward to reading your posts to The Total Package as well as those from other like minded copywriters. I was disappointed when Clayton made the decision to discontinue his blog. What a profound loss for his readers. Thanks for sharing the mind-blowing interview with him.

Daniel,

Wanna know how I came to learn about Clayton?

Through your Steal These Secrets promotion all those years ago.

True story.

Thanks for sharing.

And take care of yourself.